Beethoven is one of my favorite composers. As I am writing, I am listening to the Triple Concerto. It reminds me of a performance that I attended. The cello lead the music and joined by the piano. The conductor watched the cellist to have the orchestra join. The conductor is not the sole focal point throughout the performance. It was very interesting.

Beethoven is one of my favorite composers. As I am writing, I am listening to the Triple Concerto. It reminds me of a performance that I attended. The cello lead the music and joined by the piano. The conductor watched the cellist to have the orchestra join. The conductor is not the sole focal point throughout the performance. It was very interesting.

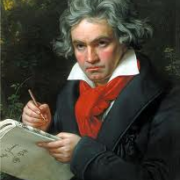

Ludwig Van Beethoven, widely considered the greatest composer of all time, was born on or about December 16, 1770 in the city of Bonn (with a population of about 10,000) in the Electorate of Cologne, a principality of the Holy Roman Empire. He was named after his grandfather, a bass player at court, and later, a music director of the chapel. His father, Johann, was a tenor in the same musical establishment, and married Maria Magdalena Keverich in 1767; she was the daughter of the head chef at the court. The mother gave birth to seven children, but only Ludwig, and two younger brothers: Caspar Anton Carl, and Nikolaus Johann survived the infancy. Ludwig Beethoven was heavily influenced by the family and the sisters-in-law in his life.

Beethoven’s mother was a slender, genteel, and deeply moralistic woman. She was one of the most radiant figures in Beethoven’s childhood. Ludwig called her “my best friend.” His father, Johann, was a mediocre court singer better known for his alcoholism than any musical ability. However, Beethoven’s grandfather was Bonn’s most prosperous and eminent musician, a source of endless pride for young Ludwig. Sometime between the births of his two younger brothers, Beethoven’s father began teaching him music with an extraordinary rigor and brutality that affected him for the rest of his life. Neighbors provided accounts of the small boy weeping while he played the clavier, standing atop a footstool to reach the keys, his father beating him for each hesitation or mistake. Ludwig also took lessons from local teachers around town. His father noticed the musical talents in him and tried to imitate the success story of Mozart before him. In March 1778, Johann forces Ludwig to hold a concert in Koeln claiming that Beethoven was six (he was seven) on the posters. According to Gerhard von Breuning, Ludwig soon became a tremendous pianist, but never had any particular ability on violin even though he played it when he was young.

Sometime after 1779, Beethoven began his studies with his most important teacher in Bonn Christian-Gottlob Neefe, the musical director of the national theatre in Bonn. As a true scholar, Neefe became a mentor for Beethoven. Neefe taught Beethoven composition, and had helped him write his first published composition: a set of keyboard variations. His most important compositions of this earliest period were the three piano Sonatas dedicated to the Elector Maximilian Friedrich in 1783, at age 13. Maximilian Frederick noticed Beethoven’s talent early, subsidized financially and encouraged the young man’s musical studies. Unlike Mozart, who was blessed with a mercurial temperament and spontaneous flow of musical notes, Beethoven had to work extremely hard at his compositions, sketching and polishing his works over and over again until he considered them finished; this was a trait of Beethoven’s entire career. At the age of 16, Ludwig already had somewhat of a reputation in Bonn. He taught music lessons and held concerts at aristocratic residences, as well as at court. His fervent harpsichord improvisations held his audience in complete awe.

Already an ardent Mozart fan, Beethoven decides to go to Vienna in 1787, in order to study with Mozart. After having listened to him, Mozart said: “watch out for that boy. One day he will give the world something to talk about”. Beethoven returned home when learned that his mother was severely ill. His mother died shortly thereafter, and his father lapsed deeper into alcoholism. As a result, Beethoven became responsible for the care of his two younger brothers at age 16. He spent his next five years at Bonn till his father died. In November 1972, Beethoven moved to Vienna where he studied and learned from the best, rose to fame, then composed the great music work till he died.

Beethoven received financial supports from many people in his career. Prince Karl Lichnowsky in Vienna was one of the most significant aristocratic supporters of Beethoven in his early career. Prince Lichnowsky enabled Beethoven to study with Haydn, Salieri, and Albrechtsberger among others. “Mozart and Haydn, his greatest predecessors, served as a paradigm of creative work in the new direction of Classicism. Albrechtsberger thoroughly taught him the art of counterpoint, which brought Beethoven his glory. Salieri taught the young composer the artistic matters of the bourgeois musical tragedy. Alois Forster taught him the art of composition with quartets. In other words, the genius musician voraciously absorbed not only the progressive music of his time, but also the richest creative experience of the most erudite contemporary composers. The musical knowledge he acquired and interpreted, together with an unmatched capacity to constantly work, makes Beethoven one of the most knowledgeable composers of his time.“ Beethoven was a difficult student as noted by Ferdinand Ries, Haydn, Salieri and Albrechtsberger, all said, “Beethoven was always so stubborn and self-willed that he had to learn from his own bitter experience what he had never been willing to accept in the course of his lessons.” Apparently, Beethoven is not being taught, but learned from experiments, and failures. Of course, we still should give credits to his teachers for their guidance.

When Haydn returned from London to Vienna in late summer of 1795, he and Beethoven often appeared together, Haydn conducting and Beethoven playing piano. Beethoven established himself to be not only a successful pianist but a highly successful composer. In February 1796, Beethoven went on tour in Prague and Berlin accompanied by prince Lichnowsky. He was very successful in both cities.

Around 1796, by the age of 26, Beethoven began to lose his hearing. He suffered from a severe form of tinnitus, a “ringing” in his ears that made it hard for him to hear music; he also avoided conversation. The cause of Beethoven’s deafness is unknown. The explanation from Beethoven’s autopsy was that he had a “distended inner ear,” which developed lesions over time.

Beethoven’s compositional career is said to be divided into three periods (early, middle, and late). The early period ends at 1802, and a year later begins the next period of Beethoven’s career. With premieres of his First and Second Symphonies in 1800 and 1803, Beethoven became regarded as one of the most important of a generation of young composers following Haydn and Mozart.

As early as 1801, Beethoven wrote to friends describing his symptoms of hearing loss and the difficulties they caused in both professional and social settings. His middle period began shortly after Beethoven began realizing he began to be going deaf. This period is known for its large-scale works that express heroism and struggle. Many of these pieces have become quite famous. His middle period works include six symphonies, two more piano concertos, the triple concerto, and a violin concerto, five string quartets, the next seven piano sonatas, the “Kreutzer” Violin Sonata, and Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio.

Beethoven’s importance as a composer was widely acknowledged in his lifetime and all but universally accepted after his death. His influence was incalculable. But an influential composer is not necessarily a beloved one. Beethoven was never married, but women had a huge influence and impact on his music and life. There were great stories for the women behind works including Moonlight Sonata and Diabelli Variations Op 120 for Eternally Beloved Antonie von Brentano. Josephine Brunsvik was another candidate for the intended recipient of the Immortal Beloved letter by most contemporary scholars.

In Memories of Beethoven, Gerhard von Breuning wrote, “My mother once wondered out loud to my father how it was possible Beethoven could be attractive to women, when he was neither handsome nor elegant, in fact was unkempt, even wild in appearance. My father answered, “And yet he was always successful with women.” – There was always in Beethoven a noble elevated sensitivity, which women perceived, whether in relationships of friendship or of love. – Breuning continued, “the truth about Beethoven’s character is that he had these traits: great nobility and tenderness, with an easily excitable temperament, mistrust, withdrawal from the world around him, together with a penchant for sarcastic wit.” We can appreciate that his personality was strongly related to his childhood and his deafness.

After a failed attempt in 1811 to perform his own Piano Concerto No. 5 (the “Emperor”), which was premiered by his student Carl Czerny in 1812, he never performed in public again. Every portrait of Beethoven seems to drive home the impression that he was a composer whose music was tempestuous, brooding and muscular. And while that was certainly the case, the masterful Emperor Piano Concerto (serene second movement) is proof of the tenderness and beauty that runs like a thread through this great man’s music. Apparently, the work’s nickname derived not from Beethoven but from a comment made by one of Napoleon’s officers, who was stationed in Vienna at the time. It was ‘an emperor of a concerto’, the man supposedly exclaimed. Indeed it was. And the name has stuck ever since.

By 1814 however, Beethoven was almost totally deaf. He was no longer able to carry on conversations with visitors, who were forced to communicate with him in writing after 1818. On top of his hearing loss, Beethoven had another problem in his relationship with his nephew, Karl. Beethoven spent a fortune to care for his brother Carl, ill from tuberculosis, for some time. After Carl died in November 1815, Beethoven immediately became embroiled in a protracted legal dispute with Carl’s wife Johanna over custody of their son Karl, then nine years old. While Beethoven was successful at having his nephew removed from her custody in February 1816, the case was not fully resolved until 1820. Karl proved to be unstable and a continuing source of worry to an already troubled man.

Beethoven’s Late Period began around 1815. Works from this period are characterized by their intellectual depth, their formal innovations, and their intense, highly personal expression. Beethoven began sketches for the Ninth Symphony in 1818. From 1820, Beethoven was working on the Missa Solemnis for the enthronement of Archduke Rudolph as Archbishop of Olmütz but it was not ready for the occasion – it was completed in 1821. The Ninth Symphony and the Missa Solemnis were premiered in Vienna on May 7th 1824 at the Karntnertor Theater. At the beginning of every part, Beethoven, who sat by the stage, gave the tempos. The success was smashing. At the end of the ” Academy “, Beethoven received standing ovations. But word has it that he had his back to the public, plunged in deep thought in the silence caused by his deafness and could not see the audience. So, then, Caroline Unger, the young alto singer, took the composer’s hand and turned him to the public. The whole audience acclaimed him through standing ovations five times; there were handkerchiefs in the air, hats, raised hands, so that Beethoven, who could not hear the applause, could at least see the ovation gestures. The theatre house had never seen such enthusiasm in applause.

At that time, it was customary that the imperial couple be greeted with three ovations at their entrance in the hall. The fact that a private person, who wasn’t even employed by the state, and all the more, was a musician (class of people who had been perceived as lackeys at court), received five ovations, was in itself inadmissible, almost indecent. Police agents present at the concert had to break off this spontaneous explosion of ovations. Beethoven left the concert deeply moved.

The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung gushed, “inexhaustible genius had shown us a new world,” and Carl Czerny wrote that his symphony “breathes such a fresh, lively, indeed youthful spirit […] so much power, innovation, and beauty as ever [came] from the head of this original man.

The Ninth Symphony reached the pinnacle of symphony at the time. With the rise of established professional orchestras, the symphony assumed a more prominent place in concert life between approximately 1790 and 1820. The most important symphonists of the latter part of the 18th century are Joseph Haydn, who wrote at least 108 symphonies over the course of 36 years (Webster and Feder 2001), and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who wrote at least 56 symphonies in 24 years (Eisen and Sadie 2001). Beethoven dramatically expanded the symphony. His Symphony No. 3 (the Eroica), has a scale and emotional range that sets it apart from earlier works. His Symphony No. 5 is arguably the most famous symphony ever written. His Symphony No. 6 is a programmatic work, featuring instrumental imitations of bird calls and a storm, and a convention-defying fifth movement. His Symphony No. 9 takes the unprecedented step (for a symphony) of including parts for vocal soloists and choir in the last movement, making it a choral symphony.

Beethoven was bedridden for most of his remaining months since December 1826, and many friends came to visit. He died on 26 March 1827 at the age of 56 during a thunderstorm. Beethoven was attracted to the ideals of the Enlightenment. He was concerned with the social affairs, be-friend with scholars, and studied their work including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Johann Friedrich von Schiller among others. The life of Beethoven resembles those tragic heroes in Greek mythology who suffer much while they were alive, but had long lasting impacts to mankind after their death. Hearing loss started around age 26 and most of his great works were completed with some level of deafness. How cruel and what a joke for a musician and composer that cannot hear? The fact that Beethoven lived through with the handicap and produced wonder music is inspirational by itself. He had lost hearing completely when he composed the Ninth Symphony, so we can say that he did it with his heart rather than the physical senses. It is a miracle indeed.

The Ninth Symphony is the largest piece of all Beethoven’s work and is so popular that the music industry went in length to make sure the Compact Disc Digital Audio standard would accommodate the complete Ninth on one disc for over 70 minutes in 1980’s. The impact of Beethoven carried through in these days as illustrated in this example.

For Further Reading:

Written in April, 2013